Supply Chain Risks Exist In The Cyber World Too

Late last week, internet service provider Cloudflare disclosed that a software bug allowed its system to embed bits of sensitive customer data in as many as 120,000 web pages it served per day for the past five months.

Even though the resulting damage likely will be minimal, the story serves as a reminder about the breadth of risks companies must manage.

You’re Accountable For Your Cyber Supply Chain

A company’s cyber supply chain can harbor just as much brand risk as supply chains in the brick and mortar world. In the 1990s, apparel firms learned that consumers held them accountable for their global supply chains, which were very complex and in some cases involved some unsavory subcontractors several levels down in the chain. Among other things, the melamine crises of the last decade proved the same is true in the consumer products industry.

In the constant battle to maintain security of information and cyber systems, companies will be held accountable for the integrity and security of their suppliers’ systems. Cloudflare is getting the news coverage now, but if anything really bad happened as a result of this situation, it would be the company’s clients – such as Uber, Cisco, Nasdaq, OkCupid, and Salesforce – whose brands could sustain the damage.

Teams responsible for cyber security and brand protection at major companies need to include this in their risk identification and mitigation calculus, as well as their crisis preparedness plans.

Putting It All In Context

Cloudflare handles about 10 percent of all internet traffic – billions of page requests every day. According to the company, the bug affected only one in every 3.3 million page requests. And when it did happen, the embedded private information would most likely have gone unnoticed or been unintelligible to the recipient.

Furthermore, the company responded immediately, issuing a preliminary fix within an hour and providing a permanent patch within seven hours, according to Wired.

Still, a number of Cloudflare’s corporate clients will have to make determinations about whether to notify their customers.

Please Ask Our Trade Association

A friend asked me this week how to determine when a company should respond to a media inquiry about an issue and when to kick the question to the industry association’s press office. Quite often, the association is in a much better position to handle challenging issues in the press because they can do so without attaching a specific brand to the story. Think about the American Beverage Association’s handling of media inquiries about sugary drinks on behalf of Coke, Pepsi, and Dr. Pepper.

Generally, media inquiries about issues that involve downside or potential for criticism should be referred to the industry association, unless:

- The company has a differentiating position on the particular issue for which it wants publicity (i.e., taking a leadership position supports a concrete business objective)

- The issue affects the company disproportionately to the rest of the industry (i.e., specifically affects the company more than competitors, as might be the case if the company has a majority share of the market or dominance in an important geography), such that not participating would make the company look noticeably absent from the story or create the perception that the company is hiding behind the trade association

When faced with a challenging media question about an industry issue, consider the following to determine whether the company or the association should respond:

- Is this an industry issue or a company issue?

- Could the association provide a credible answer?

- Do we have any interest in leading on this issue?

- Are we differentiated on this issue in a way that requires a response?

- Would we look like we’re hiding behind the association if we defer to them? (How conspicuous would our absence be?)

- How will we be positioned in the story? Best case? Worst case?

- Could it substantially improve our positioning if we were quoted?

- How would competitors perceive us if we were quoted in the story? How about the association?

- Do we set any unnecessary precedents in term of our willingness to respond in the future by responding to this inquiry with a statement or a quote?

- Do we actually have something to say about the issue that’s newsworthy, important to publicize, credible, and quotable? Or are we trying too hard because we feel some media relations obligation?

Finally, it’s crucial to be able to explain these decisions to management. Often, company bosses wonder why the company wasn’t quoted in a story about an important issue. Just as they aided the initial decision, the answers to the questions above could help justify to the CEO how the inquiry was handled.

Activists Find Their Mojo

Three new Greenpeace campaigns suggest the major activist organizations are once again targeting global brands to drive awareness about issue campaigns.

In June, Greenpeace held a demonstration against Mattel that included hanging a giant banner on the side of the company’s headquarters. The stunt, which got international media coverage, was part of the group’s campaign against the toy industry, alleging the industry buys packaging from a company responsible for deforestation in Indonesia. The campaign also targets Hasbro, Lego, and Disney.

In Europe, the group launched a campaign against VW claiming the company opposes legislation that would raise auto emissions standards by 2020. The campaign video, a parody of VW’s 2011 Star Wars Super Bowl ad, features the Death Star emblazoned with the VW logo, and a demonstration in London featured street-canvassing stormtroopers.

Screen-grab from Greenpeace's VW campaign video.

On July 12, Greenpeace launched a campaign alleging Nike and Adidas permit their suppliers in China to discharge hazardous chemicals into the Yangtze and Pearl river deltas. The campaign includes a viral video, challenging the companies to ensure their supply chains don’t contribute to water pollution.

Since the start of the recession, these types of campaigns have been rare. Most activist groups have focused on local issues: protesting the siting of a new factory, attacks on local power utilities, a demonstration against a proposed dam, and the like. When donations slow, activist groups retrench just like everyone else, and when voters are primarily focused on the economy, it’s easier to get their attention with issues that are local and tangible.

Likewise, most companies in recent years have dedicated their public affairs resources to legislative and regulatory affairs rather than activist issues. But, these new campaigns suggest it’s again time for issues managers to consider how activists might target company brands. Those who don’t might suddenly find someone using their brand to explain to people why they should quit buying the company’s products.

Cyclical Forces And The Crises of 2010

Devastating news about Johnson & Johnson, Toyota, BP, and Goldman Sachs – to name just a few – dominated headlines as much in 2010 as lousy economic news. But it’s hardly a coincidence that crises have been more prevalent in the wake the dramatic economic contraction we’ve faced.

Recession certainly exposes the financially weak and the criminal. In 2002 and 2003, Enron, WorldCom, and others collapsed amid accounting scandals. This time around, Bernie Madoff was the first of a handful of Ponzi scheme managers to face perp walks. And Lehman Brothers and AIG were revealed to be the weakest players in their respective markets as the dominos fell after the mortgage market collapsed.

But 2010 has been perilous for businesses across all sectors, including some of the best run companies in business, and that’s typical of recession and post-recession years. Consider some cyclical elements that make crises more likely in the aftermath of economic downturns:

Internal – Belt-tightening:

- Layoffs – Workforce reductions leave companies with fewer people to do the work, stretching those who are left behind, sometimes to the point where they simply can’t pay attention to everything all the time. Further, the stress of insecurity can fatigue employees (even in companies that haven’t done layoffs), who then seek to avoid extra responsibilities whenever possible. These factors conspire to increase the potential that something will be missed and make it more likely employees will try to avoid responsibility for fixing little things that could spiral into full-blown crises.

- Capex Investment Cuts – As plant becomes antiquated, management’s inclined to stretch it as far as possible before approving funds for upgrades. Sometimes the gamble works, but other times, it can lead to breakdowns in significant parts of the operation.

- Operating Cost Reductions – As CFOs pare funding for daily operations, it becomes more likely that crucial departments, such as quality assurance, get shortchanged. Managers’ decisions about where to cut budgets are never fun, and ultimately some cuts need to be made. But, each cut produces a corresponding change in the risks the company faces. Unfortunately, risk management and crisis preparedness may also face cuts, making it less likely the company can detect changes in its risk profile and respond effectively to crises.

- Supply Chain Price Pressure – Procurement departments use their market power to force supplier prices down as much as possible, exacerbating the pressures on vendors and suppliers.

External – Police Actions, Politics, and Shakedowns:

- Government Activism – Government officials and regulators turn activist, policing some real problems and exploiting populist sentiments to win political favor with frustrated voters. In the process, they often demonize business and politicize crises that occur.

- Legal Attacks – Trial lawyers search for opportunities to preach revenge to dissatisfied, frustrated, and angry customers, shareholders, local communities, and former employees. Sometimes these attacks are justified, but other times they’re just corporate shakedowns designed to play on the emotions of potential plaintiffs and extort money from companies using the threat of severe adverse publicity.

The Dangers of Cautious Expansion

Unfortunately, cautious expansion can be just as dangerous, if not more. Increasing volume without adding staff, increasing operating budgets, restarting capex investment, and bolstering quality assurance only adds stress to systems that are already working at or beyond capacity. As that stress increases, it’s only logical that a weak link in the chain will break eventually, plunging the company into crisis.

It’s also worth noting that expansion pressures on smaller, less-scalable businesses in a company’s supply chain can increase stress on their systems exponentially, and the company that manages the final product brand generally ends up responsible in the eyes of customers for any crises that occur.

Management decisions designed to handle to business cycle pressures create dramatic changes in company risk profiles. If companies limit their investments in risk management, they limit their abilities to detect these shifts and take appropriate actions to mitigate or transfer risks. If they limit their investments in crisis preparedness, they also limit their abilities to prepare crisis management plans for risks that must be tolerated.

Since Sarbanes-Oxley passed in 2002, CEOs have been required to sign off annually on company controls, which many experts believe include risk management and crisis preparedness. But this is the first full recession we’ve experienced under SOX, and laws may be interpreted differently across the business landscape. As the economy starts to churn in the year ahead, managers would do well to ensure they fully understand how their decisions change the risks inherent in their businesses. And, boards of directors should protect shareholders by demanding regular reports on risk management and crisis preparedness within the businesses they oversee. In doing so, they may make 2011 a better year than 2010.

Macondo And The Big “What If?”

BP’s report on what caused the explosion on the Deepwater Horizon has provoked a finger-pointing battle over who’s really to blame. But, none of this debate addresses what upsets people most about the crisis at the Macondo well. Beyond the human toll, beyond the economic and environmental damage, people are outraged that BP wasn’t prepared to respond.

To the public, it seems that no one at BP ever asked “what if?”

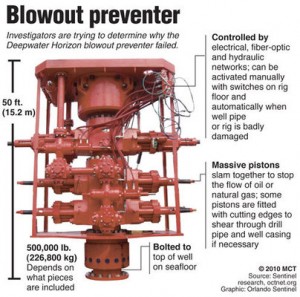

With Deepwater Horizon, BP put its crisis prevention faith in the blowout preventer. According to the Wall Street Journal, Lamar McKay, chairman and president of BP America, told a Senate panel on May 11th: “That was to be the failsafe in case of an accident.”

But many people look at images of blowout preventers and wonder why BP didn’t consider: “What if this thing fails?” Today, it seems obvious to outsiders with 20/20 hindsight that a lot could go wrong with such a complex piece of engineering. As a result, people believe that neither the company nor its regulators thought things through.

To be fair, a number of people at BP actually did raise the question. A 2007 paper co-authored by a BP engineer questioned whether blowout preventers would actually work to prevent deep water blowouts. Sadly, the What If question either wasn’t compelling to management or it wasn’t heard at all.

Blowout preventers were developed because people involved in offshore drilling asked “what if there’s a blowout?” But risk managers and crisis advisers can’t stop there. Once a new system, process, or piece of equipment gets installed, the protectors of companies have to take the question one step further: what if this new thing doesn’t work? And ultimately, good crisis advisers should help the company prepare for a scenario in which all the safeguards fail: What if the worst-case scenario happened? Would we be able to respond?

BP spokesman Andrew Gowers told the Wall Street Journal on June 29th that the company has put “significant effort and investment” into safety. After crises at Texas City and Prudhoe Bay and a near miss at Thunder Horse (among others), that’s what many Americans expected when Tony Hayward took over as CEO.

But there’s a difference between approaching safety as a series of standards to be met and creating a culture in which employees and executives compulsively ask What If and make decisions in the context of the answers.

What If questions are the bread and butter of the core protective functions in any company. These questions often deal with incredibly complex business issues, plant, and processes, and it requires a lot of experience and knowledge of the business to ask the questions effectively. In addition, the answers can have expensive ramifications, and operating executives adhering to budgets don’t like spending additional money.

But, a balance needs to be struck. The overall objective isn’t to limit the company’s ability to operate, and in fact, no level of investment can make a business completely safe and prepared. However, if a company doesn’t consider all the What If questions, there’s no way to know if its safety standards are appropriate or whether it’s operating in a risk environment that’s too dangerous.

At least, not until a crisis occurs. Then, the public will think all the answers to What If questions should have been obvious long ago.

It’s A Scary World For High-Profile Businesses

Today’s CEOs face an unprecedented set of threats that go way beyond the cutthroat competition and organizational challenges normally in the purview of corporate leaders.

- Underlying operating risks can explode into catastrophes with little or no warning.

- Political interest groups and activists attack high-profile brands to drive attention to their causes.

- News reports and scientific studies identify new health risks every day.

- Issues like global warming are changing the way consumers, governments, companies, special interests, and markets behave and interact.

- Governments are dramatically reshaping the business environment, creating political risks and operating pitfalls for companies.

- The public constantly questions whether companies are prepared for disaster.

- Minute-by-minute media reports feed the public’s insatiable appetite for stories of scandal, tragedy, incompetence, greed, and conspiracy.

- Shareholders can turn instantly on companies that don’t create wealth each quarter.

As they face these circumstances, how companies interact with their stakeholders makes all the difference. When successful, they can reassure people and build loyalty, even in bad situations. When they fail, they may alienate customers, employees, or business partners enough that the business can’t survive. After all, companies can’t exist if their customers, employees, and other stakeholders won’t do business with them. And government regulations, whether appropriate or not, can stifle a company’s ability to turn a profit.

Risks, Crises, Contentious Issues, and What Companies Can Do About Them

To minimize the impact of risks, crises, and social issues, corporate leaders need to several things:

- Assign a senior executive formal responsibility for:

- Coordinating all the protective functions within the company

- Building and maintaining a comprehensive corporate perspective about the full spectrum of threats that could affect the business

- Establish a system for listening to stakeholders and anticipating issues and potential crisis scenarios

- Determine and make the appropriate investments in preparedness

- Ensure all employees take responsibility for safety and protecting the company

- Identify opportunities to shape social issues either to the company’s benefit or to minimize the issues’ potential impact

- Retain external crisis management and issues management advisers to provide unvarnished counsel to management

With these ideas in mind, The Crisis Adviser offers an opportunity to delve into these ideas more thoroughly. The Advisory section will include thoughts on current events in the News & Analysis posts, as well as more theoretical posts in the category Theory & Practice. I hope you find it thought provoking and helpful. And if you have any thoughts or questions, feel free to contact me or post your thoughts on the site.